The Papuan Volunteers Corps was set up in February 1961 to ensure Papuan involvement in protecting the interests of former Dutch new Guinea. It was primarily established for political reasons as part of the Ten Year Plan in 1960 by Cabinet De Quay. Military motives were of secondary interest. The Dutch Government wanted to accelerate the development of the colony in preparation for New Guinea’s independence and as such to keep it from being taken over by the Indonesians. The Papuan Volunteers Corps was to promote the knowledge and development of the social infrastructure by including civilian as well as military information as part of the training. The Volunteer Corps was to play a pivotal role in an independent West Papua. The

The Papuan Volunteers Corps was set up in February 1961 to ensure Papuan involvement in protecting the interests of former Dutch new Guinea. It was primarily established for political reasons as part of the Ten Year Plan in 1960 by Cabinet De Quay. Military motives were of secondary interest. The Dutch Government wanted to accelerate the development of the colony in preparation for New Guinea’s independence and as such to keep it from being taken over by the Indonesians. The Papuan Volunteers Corps was to promote the knowledge and development of the social infrastructure by including civilian as well as military information as part of the training. The Volunteer Corps was to play a pivotal role in an independent West Papua. The  native troops were essential for patrolling the jungle and swamps and as such they were important for the tasks to be done by the Dutch soldiers in the Army and Marine Corps. However, their plans did not come to fruition because the Indonesian president Sukarno stakes his claim: the Dutch colony was to become a part of the newly formed Republic of Indonesia. This led to a political conflict between Indonesia and the Netherlands. The Papuan Volunteers Corps, a unique component of the Dutch forces, did not survive the political changes and the whole project had to be terminated. The Papuan Volunteer Corps was disbanded when Indonesia took over from the interim administration by the United Nation on 1 May 1963. The Papuan troops stayed behind without a job.

native troops were essential for patrolling the jungle and swamps and as such they were important for the tasks to be done by the Dutch soldiers in the Army and Marine Corps. However, their plans did not come to fruition because the Indonesian president Sukarno stakes his claim: the Dutch colony was to become a part of the newly formed Republic of Indonesia. This led to a political conflict between Indonesia and the Netherlands. The Papuan Volunteers Corps, a unique component of the Dutch forces, did not survive the political changes and the whole project had to be terminated. The Papuan Volunteer Corps was disbanded when Indonesia took over from the interim administration by the United Nation on 1 May 1963. The Papuan troops stayed behind without a job.

Content:

1. Papuan Battalion a precursor to Volunteer Corps

2. Diplomatic negotiations

3. Papuan Voluntary Corps played down

4. Dutch officers lead Papuan Volunteer Corps

5. Arfai Army Camp

6. Papuan soldiers unbeatable in the bush

7. Five platoons trained in record time

8. Papuan soldiers against infiltrators on Gag Island

9. Handover to UNTEA

10. Links

11. Sources

1. Papuan Battalion a precursor to Volunteers Corps

The Papuan Volunteers Corps can be regarded as an indirect continuation of the Papuan Battalions* within the army which operated during WW II and which was disbanded in1948. At the end of 1949, the defence was in the hands of two platoons of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNI), a platoon of New Guinea Army soldiers and two platoons of Papuan soldiers, all under the command of Major John Eechoud. Returning Papuan soldiers are added to the two Papua platoons, making it a company of 142 men. Many Papuans find the militaristic way of training very difficult. The KNIL mentality was very different to that of the Papuan soldiers. They were used to guerrilla warfare: ambush, waiting a

The Papuan Volunteers Corps can be regarded as an indirect continuation of the Papuan Battalions* within the army which operated during WW II and which was disbanded in1948. At the end of 1949, the defence was in the hands of two platoons of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNI), a platoon of New Guinea Army soldiers and two platoons of Papuan soldiers, all under the command of Major John Eechoud. Returning Papuan soldiers are added to the two Papua platoons, making it a company of 142 men. Many Papuans find the militaristic way of training very difficult. The KNIL mentality was very different to that of the Papuan soldiers. They were used to guerrilla warfare: ambush, waiting a  while, shooting and then retreating. In its hay-day, the Papua battalion consisted of more than 1000 men but towards the end of its existence it counted no more than about 100 to 150 soldiers. The battalion continued up until the New Guinea Army as a whole was disbanded at the end of 1955. For the purpose of law enforcement, the Algemene Politie (Police Force) was present and they had to make do with any weapons that were around at the time. At the beginning 150 Dutch KNI L carbines were in use. However, from 1960 onwards the police was equipped with armament which largely corresponded with that of the Papuan Volunteer Corps, namely Papua Mauser rifles and Uzi machine guns.

while, shooting and then retreating. In its hay-day, the Papua battalion consisted of more than 1000 men but towards the end of its existence it counted no more than about 100 to 150 soldiers. The battalion continued up until the New Guinea Army as a whole was disbanded at the end of 1955. For the purpose of law enforcement, the Algemene Politie (Police Force) was present and they had to make do with any weapons that were around at the time. At the beginning 150 Dutch KNI L carbines were in use. However, from 1960 onwards the police was equipped with armament which largely corresponded with that of the Papuan Volunteer Corps, namely Papua Mauser rifles and Uzi machine guns.

2. Diplomatic negotiations

The Ten Year Plan of Cabinet De Quay proposed to accelerate self-determination of Papuans because of the threat and growing military potential of Indonesia and the increasing political isolation of the Netherlands from the rest of the world and from the United States in particular. In March 1959 Peter Platteel, the governor of Dutch New Guinea, recommended that the Papuan Volunteer Corps be established. On the basis of this advice the Secretary of State, Theo Bot, put this idea to Cabinet De Quay on 11 December 1959. The Cabinet agreed with it in principle but it took until February 1961 for Queen Juliana to confirm it officially by Royal Decree. On 28 July 1961 Prime minister de Quay outlined the situation as follows: “Cooperation from the United States can only be

The Ten Year Plan of Cabinet De Quay proposed to accelerate self-determination of Papuans because of the threat and growing military potential of Indonesia and the increasing political isolation of the Netherlands from the rest of the world and from the United States in particular. In March 1959 Peter Platteel, the governor of Dutch New Guinea, recommended that the Papuan Volunteer Corps be established. On the basis of this advice the Secretary of State, Theo Bot, put this idea to Cabinet De Quay on 11 December 1959. The Cabinet agreed with it in principle but it took until February 1961 for Queen Juliana to confirm it officially by Royal Decree. On 28 July 1961 Prime minister de Quay outlined the situation as follows: “Cooperation from the United States can only be  obtained via a procedure acceptable to the Indonesians and such a procedure is by definition unacceptable for the Netherlands”.

obtained via a procedure acceptable to the Indonesians and such a procedure is by definition unacceptable for the Netherlands”.

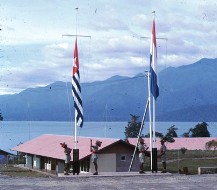

In 1961 a diplomatic proposal from Minister Luns from Foreign Affairs was being negotiated to place New Guinea under temporary administration of the United States before handing it over to the Papuans. Of course Indonesia did not agree with this proposal as it would eliminate them altogether. The Netherlands however continued further down the path of self-determination by allowing the Papuans their own elected parliament, the New Guinea Council, their own flag and national anthem.

3. Papuan Volunteers Corps played down

In a report written in 1960 by Van Heuvel, the commander of the Papuan Volunteer Corps, he recommended that the Corps should consist of about 200 soldiers initially and grow to 660 over time. However Platteel, the governor of Dutch New Guinea, thought that the Corps should consist of between 300 men and 450 men. In 1960 one million dollars was made available by Defence to take care of the start-up costs. The overall costs were mainly to be financed by Internal Affairs. Within the Ten Year Plan a total of 8, 5 million guilders was budgeted for the three years from 1960 to 1962. However, the minister of Defence did not want to publicise the fact that the Voluntary Corpse was being established and on 7 January 1960, he asked the commander of the Navy not to mention the plans in public.

In a report written in 1960 by Van Heuvel, the commander of the Papuan Volunteer Corps, he recommended that the Corps should consist of about 200 soldiers initially and grow to 660 over time. However Platteel, the governor of Dutch New Guinea, thought that the Corps should consist of between 300 men and 450 men. In 1960 one million dollars was made available by Defence to take care of the start-up costs. The overall costs were mainly to be financed by Internal Affairs. Within the Ten Year Plan a total of 8, 5 million guilders was budgeted for the three years from 1960 to 1962. However, the minister of Defence did not want to publicise the fact that the Voluntary Corpse was being established and on 7 January 1960, he asked the commander of the Navy not to mention the plans in public.

The Corps was an independent section of the Dutch Armed Forces and this meant that the Papuan soldiers were formally employed by the Netherlands. There was a squabble about whether or not it was acceptable for these soldiers to get a Dutch  status while Government officials did not have this status. Apart from this, the status of the Papuan Volunteers Corps within the military structure had not been entirely clear right from the beginning. According to the initial instructions the Corpse was directly under the command of the Governor, who had the ultimate responsibility for the armed forces in Dutch New Guinea. Yet, the actual commander of the armed forces in New Guinea (who was known as COSTRING) felt that the Corps should be under his command. In reality the operational command of these platoons did rest with COSTRING when it came to deploying them against any infiltrators.

status while Government officials did not have this status. Apart from this, the status of the Papuan Volunteers Corps within the military structure had not been entirely clear right from the beginning. According to the initial instructions the Corpse was directly under the command of the Governor, who had the ultimate responsibility for the armed forces in Dutch New Guinea. Yet, the actual commander of the armed forces in New Guinea (who was known as COSTRING) felt that the Corps should be under his command. In reality the operational command of these platoons did rest with COSTRING when it came to deploying them against any infiltrators.

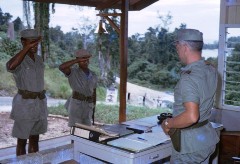

4.Dutch officers lead Papuan Volunteers Corps

The Papuan Corps is headed by officers from 3 different sections of the military: 20 men from the Royal Navy, 13 from the Royal Army and another 11 from the Dutch Royal Air Force. W.A. van Heuvel, lieutenant colonel of the Navy, became the commander of the Papuan VolunteersCorps that was being set up. Recruitment began in September 1961 and there was such an interest among the Papuans that the number of candidates was way higher than the number of actual available places. Thousands of men lined up in front of the Police office in Hollandia, while only 30 men were to be selected at this location. In total 200 men were selected and these started their training on 1November 1961. Many of the recruits regarded the new corps as a precursor to a national army of their own. They firmly believed that New Guinea was to become independent, especially when the newly elected New Guinea Council decided to change the name of the region to West Papua. One of the recruits remarked: ‘T he flag has been chosen, we already have a national anthem, and so independence is sure to follow.” After all, Queen Juliana had promised self-determination for the Papuans in 1960 and this was to be put into practice by the new Guinea Council or ‘Nieuw Guinea Raad’ as it was called in Dutch.

The Papuan Corps is headed by officers from 3 different sections of the military: 20 men from the Royal Navy, 13 from the Royal Army and another 11 from the Dutch Royal Air Force. W.A. van Heuvel, lieutenant colonel of the Navy, became the commander of the Papuan VolunteersCorps that was being set up. Recruitment began in September 1961 and there was such an interest among the Papuans that the number of candidates was way higher than the number of actual available places. Thousands of men lined up in front of the Police office in Hollandia, while only 30 men were to be selected at this location. In total 200 men were selected and these started their training on 1November 1961. Many of the recruits regarded the new corps as a precursor to a national army of their own. They firmly believed that New Guinea was to become independent, especially when the newly elected New Guinea Council decided to change the name of the region to West Papua. One of the recruits remarked: ‘T he flag has been chosen, we already have a national anthem, and so independence is sure to follow.” After all, Queen Juliana had promised self-determination for the Papuans in 1960 and this was to be put into practice by the new Guinea Council or ‘Nieuw Guinea Raad’ as it was called in Dutch.

5.Arfai Training Camp

The successful candidates came to Manokwari from all over New Guinea to start the three year course of civilian and military training. They were stationed at the newly built Arfai Camp, 15 km south of Manokwari and ideally situated on sloping terrain with the sea on one side and the Arfak Mountain Range on the other. Each soldier was armed with a rifle and a machete and earned 34 guilders per month, with an additional surcharge of one guilder a day when he was on patrol. Their Khaki uniform consisted of a jacket, a pair of trousers or shorts and

The successful candidates came to Manokwari from all over New Guinea to start the three year course of civilian and military training. They were stationed at the newly built Arfai Camp, 15 km south of Manokwari and ideally situated on sloping terrain with the sea on one side and the Arfak Mountain Range on the other. Each soldier was armed with a rifle and a machete and earned 34 guilders per month, with an additional surcharge of one guilder a day when he was on patrol. Their Khaki uniform consisted of a jacket, a pair of trousers or shorts and  green boots suitable for the jungle. In this army outfit with its shiny buttons, red epaulettes, a red sash and a whistle on a red and black cord, the soldiers looked really smart. It was worn too when they went out, but in that case the army cap was replaced by a felt hat decorated with the Corps’ emblem and a red cockade with a plume of black feathers.

green boots suitable for the jungle. In this army outfit with its shiny buttons, red epaulettes, a red sash and a whistle on a red and black cord, the soldiers looked really smart. It was worn too when they went out, but in that case the army cap was replaced by a felt hat decorated with the Corps’ emblem and a red cockade with a plume of black feathers.

Everything at Arfai Camp was new, from the galley equipment to the blue swimming trunks for the soldiers. Because of the rather British appearance of the army tunic, the Corps was soon nicknamed The Queens Own Arfak Highlanders.

6. Papuan soldiers unbeatable in the bush.

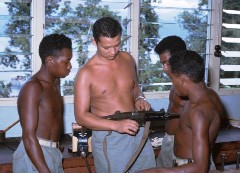

The Papuan Volunteers Corps was originally a training unit. The first training was launched on 1 November. The Papuan soldiers were organized into ten training classes. Under the leadership of Colonel van Heuven, the Corps develops into 5 platoons of 37 men each, 25 of which were Papuan. These platoons were led by Dutch commanders and their assistant commanders. As bush soldiers, the Papuans excelled and could not be matched. The Papuans were armed with Mauser Rifles which were modified FN carbines of the Dutch Police. A special bayonet, manufactured by a Dutch army Factory, had been added to the modified versions, as well as a special gadget for the shooting of grenades. The officers were equipped with the M.46 Browning pistol. From May 26 onwards the unit also used Uzis which had already been introduced to the Dutch Army earlier on that year. Each platoon had 8 Uzis and these were used by the officers. When the Corps was disbanded after the Handover of New Guinea to Indonesia there were 129 Uzis in use. In January 1962, the New Guinea Council

The Papuan Volunteers Corps was originally a training unit. The first training was launched on 1 November. The Papuan soldiers were organized into ten training classes. Under the leadership of Colonel van Heuven, the Corps develops into 5 platoons of 37 men each, 25 of which were Papuan. These platoons were led by Dutch commanders and their assistant commanders. As bush soldiers, the Papuans excelled and could not be matched. The Papuans were armed with Mauser Rifles which were modified FN carbines of the Dutch Police. A special bayonet, manufactured by a Dutch army Factory, had been added to the modified versions, as well as a special gadget for the shooting of grenades. The officers were equipped with the M.46 Browning pistol. From May 26 onwards the unit also used Uzis which had already been introduced to the Dutch Army earlier on that year. Each platoon had 8 Uzis and these were used by the officers. When the Corps was disbanded after the Handover of New Guinea to Indonesia there were 129 Uzis in use. In January 1962, the New Guinea Council  called for the Corps to be expanded. Colonel van Heuven responded with the message that the training time could be reduced and that the Corps should expand to the original 660 he had asked for and that it should reach a total of 1200 by the end of the three year training period. In addition, eight Papuan candidates were selected who were to be trained as officers by the end of 1962.

called for the Corps to be expanded. Colonel van Heuven responded with the message that the training time could be reduced and that the Corps should expand to the original 660 he had asked for and that it should reach a total of 1200 by the end of the three year training period. In addition, eight Papuan candidates were selected who were to be trained as officers by the end of 1962.

In September of that same year, 16 corporals were promoted to become sergeants within the Corps. At this same point in time, Indonesia decided to step up military pressure and the number and size of infiltrations were increasing as well. As a result the Dutch increased the number of troops in order to ward off a possible attack. A major military conflict seemed unavoidable.

7. Five platoons trained in record time

The Papuan Volunteers Corps in conjunction with the Marine Corps and the local police started to take action against Indonesian infiltrators that were arriving on New Guinea. After just four months of training, commander of the New Guinea Armed Forces inquired if the Papuan Corps could be deployed on short notice. Due to increasing political pressure, the Papuan Volunteers Corps would have to go into action much earlier than planned. The Corps’ commander responded by forming 5 platoons of his best recruits to be trained in no time at all for independent detection and deactivation of small groups of infiltrators out in the bush and swamps of the New Guinea jungle. In the fight against the larger groups of infiltrators, the Papuan platoons were to locate their whereabouts for the Dutch troops. Each of the five platoons consisted of 25 Papuan soldiers who were led by Dutch army personnel: one commander, four officers and six noncommissioned

The Papuan Volunteers Corps in conjunction with the Marine Corps and the local police started to take action against Indonesian infiltrators that were arriving on New Guinea. After just four months of training, commander of the New Guinea Armed Forces inquired if the Papuan Corps could be deployed on short notice. Due to increasing political pressure, the Papuan Volunteers Corps would have to go into action much earlier than planned. The Corps’ commander responded by forming 5 platoons of his best recruits to be trained in no time at all for independent detection and deactivation of small groups of infiltrators out in the bush and swamps of the New Guinea jungle. In the fight against the larger groups of infiltrators, the Papuan platoons were to locate their whereabouts for the Dutch troops. Each of the five platoons consisted of 25 Papuan soldiers who were led by Dutch army personnel: one commander, four officers and six noncommissioned  officers. From May to August these five platoons were repeatedly put into action against the infiltrators. Three platoons went in at any one time while two were catching their breath back at Arfai camp. The first platoon was armed with 8 Uzis, 22 carbines as well as four Cetme rifles that had been taken off Indonesian infiltrators in May of 1962. The officers carried Bren guns and Browning machine guns. Later a further ten Cetme Rifles were supplied to the platoons to replace four Bren guns and six Browning machine guns that were taken away to defend the Arfai Army camp. The Cetme rifles which had retractable buts were confiscated form the enemy and had Indonesian army logo on them. Some of these ended up as display items in Dutch Military Museums.

officers. From May to August these five platoons were repeatedly put into action against the infiltrators. Three platoons went in at any one time while two were catching their breath back at Arfai camp. The first platoon was armed with 8 Uzis, 22 carbines as well as four Cetme rifles that had been taken off Indonesian infiltrators in May of 1962. The officers carried Bren guns and Browning machine guns. Later a further ten Cetme Rifles were supplied to the platoons to replace four Bren guns and six Browning machine guns that were taken away to defend the Arfai Army camp. The Cetme rifles which had retractable buts were confiscated form the enemy and had Indonesian army logo on them. Some of these ended up as display items in Dutch Military Museums.

8. Papuan soldiers against infiltrators on Gag Island

The Papuan soldiers knew the jungle inside out and were therefore used to track down Indonesian infiltrators. One Papuan platoon was dropped by the marines on the island of Gag where the Indonesians were disputing Dutch occupation. The platoon had to deal to Indonesian infiltrators dropped there by President Sukarno which was an illegal action according to the Dutch. The Papuan soldiers simply waited until the enemy came out of hiding because their food supplies had run out. On 4 October 1961 the Papuans opened fire. In the next few days they captured 21 infiltrators and killed two. Officially, they were supposed to have asked for permission to attack but in a situation such as this the Papuan military felt that they had the right to act and should be able to defend their own country. The villagers on Gag agreed: they saw the men as soldiers of their own who spoke a Papuan Language just like they did.

The Papuan soldiers knew the jungle inside out and were therefore used to track down Indonesian infiltrators. One Papuan platoon was dropped by the marines on the island of Gag where the Indonesians were disputing Dutch occupation. The platoon had to deal to Indonesian infiltrators dropped there by President Sukarno which was an illegal action according to the Dutch. The Papuan soldiers simply waited until the enemy came out of hiding because their food supplies had run out. On 4 October 1961 the Papuans opened fire. In the next few days they captured 21 infiltrators and killed two. Officially, they were supposed to have asked for permission to attack but in a situation such as this the Papuan military felt that they had the right to act and should be able to defend their own country. The villagers on Gag agreed: they saw the men as soldiers of their own who spoke a Papuan Language just like they did. The Papuan Volunteers Corps also played a major role in combating various Indonesian attempts to infiltrate elsewhere on New Guinea. Among these were attempts at Waigeo, Fak Fak en Misool, Onin, Kaimana, Teminaboean and Merauke. The Papuan platoons functioned as well disciplined units moving quickly across difficult terrain. The Papuan soldiers had enormous stamina and a real spirit to fight. They often carried the heavy artillery for the Dutch soldiers who became exhausted under the trying conditions of the New Guinea jungle. The Papuans were used to being in the jungle and only needed few rations. In their opinion, the combat rations of the Dutch marines were too heavy and rather excessive. Although the Dutch military regarded the Papuan soldiers as a very welcome reinforcement, they were never officially recognised as Dutch veterans.

The Papuan Volunteers Corps also played a major role in combating various Indonesian attempts to infiltrate elsewhere on New Guinea. Among these were attempts at Waigeo, Fak Fak en Misool, Onin, Kaimana, Teminaboean and Merauke. The Papuan platoons functioned as well disciplined units moving quickly across difficult terrain. The Papuan soldiers had enormous stamina and a real spirit to fight. They often carried the heavy artillery for the Dutch soldiers who became exhausted under the trying conditions of the New Guinea jungle. The Papuans were used to being in the jungle and only needed few rations. In their opinion, the combat rations of the Dutch marines were too heavy and rather excessive. Although the Dutch military regarded the Papuan soldiers as a very welcome reinforcement, they were never officially recognised as Dutch veterans.

9. Handover to UNTEA

The elaborate plans to build up the Papuan Volunteers Corps into an independent force were abruptly halted in August 1963 by the truce with Indonesia. The Netherlands had been negotiating in 1962 about having to hand New Guinea over to Indonesia. For the Dutch Government it was unacceptable that it would go directly to Indonesia. For this reason a strategy was devised, whereby governance was first transferred to the United Nations, which then in turn would transfer this to Indonesia.

The elaborate plans to build up the Papuan Volunteers Corps into an independent force were abruptly halted in August 1963 by the truce with Indonesia. The Netherlands had been negotiating in 1962 about having to hand New Guinea over to Indonesia. For the Dutch Government it was unacceptable that it would go directly to Indonesia. For this reason a strategy was devised, whereby governance was first transferred to the United Nations, which then in turn would transfer this to Indonesia.

The Papuan Volunteers Corps was initially still part of the Dutch Armed forces but it was put under the authority of the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA) in October 1963. The Corps, the Algemene Politie (Papuan Police Force) as well as the contingent of the Indonesian infiltrators present in West new Guinea officially became part of the UNTEA. A team of eleven Dutch government officials were involved with finalising the necessary administration for the handover. During the UNTEA period the Dutch officials and their families departed (about 15000 people as did the military units (about10.000 men). Leaving behind a large amount of property. The value of this was estimated to be around 35 million euro. On 1May 1963 Indonesia took over administration of West New Guinea. The Papuan Volunteers Corps was disbanded. The new name of the western Part of the island became Irian Barat (in 1973 this was changed to Irian Jaya). Some of the members of the Corps later entered the Indonesian Army. Others set up the guerrilla warfare group, Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM), in the Birds Head Area to start the battle for independence. Among the initiators were sergeant Perminas ‘Ferry’Awom and the two brothers Lodewijk and Barens Mandatjan.

On 1May 1963 Indonesia took over administration of West New Guinea. The Papuan Volunteers Corps was disbanded. The new name of the western Part of the island became Irian Barat (in 1973 this was changed to Irian Jaya). Some of the members of the Corps later entered the Indonesian Army. Others set up the guerrilla warfare group, Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM), in the Birds Head Area to start the battle for independence. Among the initiators were sergeant Perminas ‘Ferry’Awom and the two brothers Lodewijk and Barens Mandatjan.

On 4 May 1963 president Sukarno paid an official visit to the area and nominated the Papuan politician Eliezer Bonay as governor of Irian Barat. Shortly after Sukarno prohibited all existing political parties and unofficial political activity in Irian Barat.

10. Links

- PACE website : Veteran footsteps

- YouTube film : Papoea Vrijwilligers Korps

- Link to Maritime Museum Gevechten rond het dorp Terminaboean

- Wikipedia about Papuan Volunteer Army (Papoea Vrijwilligerskorps )

- Hoe Nederland zijn Papoea-soldaten vergat. In Check Point, April/May 2003

- Indonesische para's kregen harde ontvangst. In Legerkoerier , 1962 by kapitein J. H. Buising.

- Sneuvelen voor Nederland, voor niets. In Trouw ( Dutch News paper) , 29 april 2003

- 'Papoea-veteranen verdienen erkenning'. In Trouw, 2 May 2003

- Papoea Vrijwilligers Korps, Herinneringen van de S 4 by J. H. Rooseboom

- UNTEA and UNRWI: United Nations Involvement in West New Guinea During the 1960’s by John Francis Saltford BA (Hull), MA (Kent), University of Hull, April 2000 , www.papuaweb.org

11. Sources

- Bruggen van. Casper. 2005. Vergeet ons niet: met het Papoea Vrijwilligers Korps op patrouille. Armamentaria 40 : 212-231. ISSN 0168-1672; ISBN 90-70793-28-8

- Roos de G.K.R. 1979 “De marinierskant van het verhaal.” (Account of the Papua Volunteer Corps from a marine’s perspective). The Hague:Bureau Maritiem Instituut/Ministerie van Defensie.

- Holst-Pellekaan van, R.E. , Regst de , I.C. and Bastiaans, I.F.J. 1989.“Patrouilleren voor de Papoea's: de Koninklijke Marine in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945-1960/1960-1962.” Amsterdam: Bataafse Leeuw. ISBN 9067071978.

- Peters, Theo. 1993. Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945-1962. Een na-oorlogse kroniek. The Hague: Vereniging Belangenbehartiging Militairen VBM/LKV. ISBN 90-801860-1-5

- Kock de, Pieter P. 1981. De ongelijke strijd in de Vogelkop. With notes by Ben M. Koster. Franeker: Uitgever Wever. ISBN: 90-6135-315-7

- Kock de, Pieter P. 1996. Worstelend voor de erkenning : autobiografie. Leidschendam :Pieter de Kock.:ISBN: 90-803317-2-4

- Comment en advice: Marc Lohnstein, Military History advisor of Bronbeek Museum in Arnhem